Roosevelt campaigns

from a car seat.

Photo courtesy of

the New Deal Network |

Page

1 | Page 2 | Page 3

From then on, Roosevelt fought three wars. He fought a war to bring

the U.S. economy back on track. Beginning in 1941 he fought World War II.

Finally, he continued to fight the war against poliomyelitis.

Roosevelt at the West Virginia

Foundation for Crippled Children

Photo courtesy of the

New Deal Foundation

Although he was no longer directly associated with the fund

raising—the Birthday Ball Commission had given way to the National Foundation for

Infantile Paralysis—President Roosevelt continued to be a rallying symbol for the war

on polio. He was also, in a nation that was still acquiring newly paralyzed children

(and adults) every summer, a symbol of what the disabled could be. In a nation where

the disabled had been hidden away, shunned, perhaps even institutionalized, Roosevelt was

a symbol of a person with limitations working to the full extent of his capabilities.1

The annual fund-raising was moved to movie theaters to take the pressure

off of the White House mail clerks, but the drive continued to be held at the end of the

January, to coincide with Roosevelt's birthday. Actors like Judy Garland, Mickey

Rooney, Jimmy Stewart, and Robert Young would be filmed in "live" shorts,

appealing directly to the audience. The shorts would be shown, and then the lights

would come up and ushers would collect donations in baskets. Only after the money

was collected would the feature be shown.2

One might have expected that World War II would take a toll on the

collections, and it did, although not in the way that one might have thought. With

the Depression safely behind, many people felt the warm blessing of affluence, and

continued to donate. But by 1943, there were no ushers left at the movie

theaters. All of the young men had been drafted.

The task of fundraising, like so many other civilian jobs, was turned over

to women. Roosevelt directed O'Connor to create a Women's Division, and told him

that Mary Pickford had volunteered to be the honorary director of women volunteers.3

O'Connor had no interest in organizing women, but there was no other source of labour, and

he never counted on the power of the image of almighty womanhood, mothers gathering to

raise the money that stood between America's children and The Crippler, Poliomyelitis.

The organization of the Foundation around movie stars and the common

people made it more powerful. It also made it able to stand the loss of what might

have been its most important spokesperson. Franklin Roosevelt died of a cerebral

hemorrhage at Warm Springs, Georgia, on 12 April 1945.

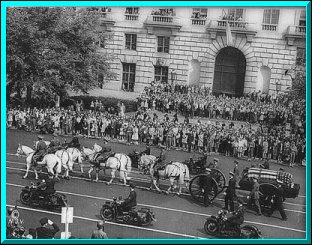

Roosevelt's body passes down Pennsylvania Avenue.

Photo courtesy of The HistoryNet

In 1964, an international agreement between U.S. President Harry S Truman

and Canadian Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson established the Roosevelt Campobello

International Park Commission to preserve the vacation home where Roosevelt was struck

down by polio and the course of history was changed forever. Twenty-eight hundred

acres are preserved in the park, along with the Roosevelt cottage. Both governments

felt the need to recognize the many contributions that Roosevelt had made to both nations.4

Page 1 | Page 2 | Page 3

Footnotes

1. Smith, Jane S. Patenting the Sun: Polio and the

Salk Vaccine. New York, New York: William Morrow and Company, Inc.

1990. p. 46.

2. idem. p. 75.

3. idem. p. 79.

4. "Home Page." Roosevelt Campobello

International Park Commission. 1997. http://www.fdr.net/.

(31 May 1999). |